China's innovation problem: weak science

Wednesday, June 8, 2016 at 5:02PM

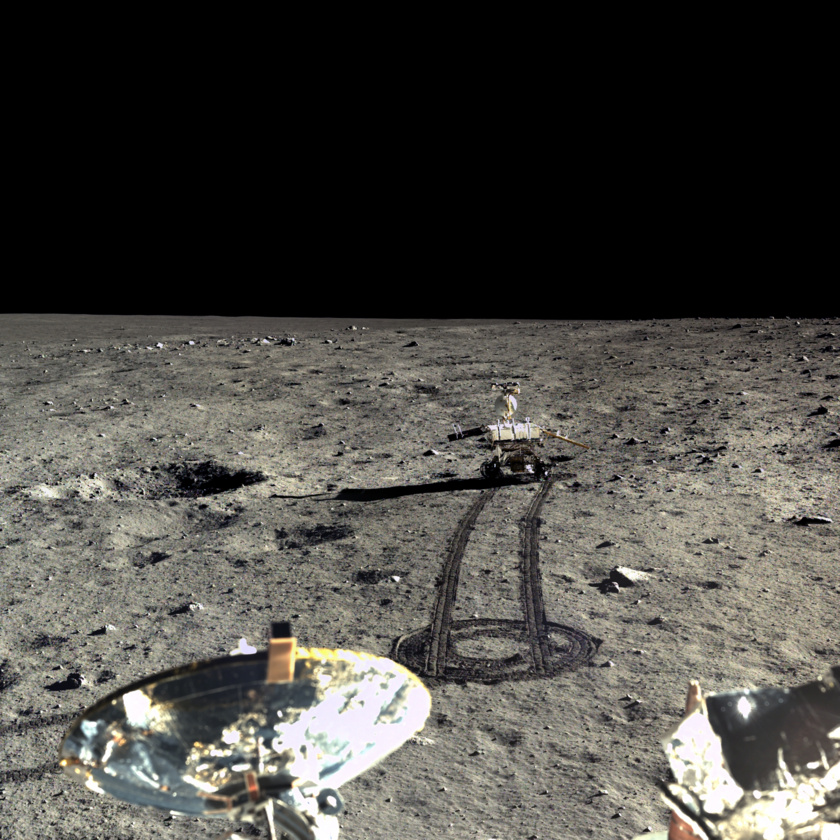

Wednesday, June 8, 2016 at 5:02PM China is racking up some impressive Big Science achievements. In the pipeline are the world's biggest radio telescope, a quantum communications network and further moonshots.

The Economist this week runs a cautious rule over some of these, observing that China’s science, like so much of the country, careers between pride and insecurity. The number of scientific papers has skyrocketed and the rate of citations has also improved markedly. But, like so much of the country, it suffers from corruption, cronyism and arbitrary government interference.

The Economist this week runs a cautious rule over some of these, observing that China’s science, like so much of the country, careers between pride and insecurity. The number of scientific papers has skyrocketed and the rate of citations has also improved markedly. But, like so much of the country, it suffers from corruption, cronyism and arbitrary government interference.

These were points made by scientists Rao Yi and Shi Yigong in an op-ed in Science four years ago, prompting sharp denials and, with unintended irony, Rao being overlooked for promotion.

Rao, Dean of the School of Life Sciences at Peking University, is one of the country’s most prominent boffins. Now, in a less contentious but still insightful essay, Rao expresses pessimism about China’s scientific prospects, citing its weak scientific tradition and the small number of students taking it up.

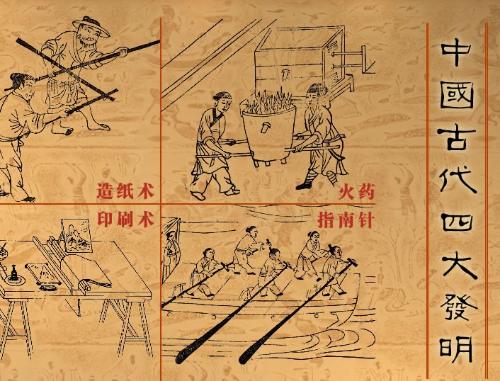

He takes aim at fallacies surrounding China’s historical scientific attainments. Chinese like to believe that up to late Ming or Qing they led the world in science, citing Joseph Needham, the British scholar who brought to light centuries of Chinese science unknown to the rest of the world and barely known to Chinese.

In fact, says Rao, China lacks a scientific tradition. Classical Chinese education emphasised literature and philosophy. Confucian texts and poetry, not the scientific rituals of observation and deduction, were paths to a successful career.

Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Space Administration / The Science and Application Center for Moon and Deepspace Exploration / Emily Lakdawalla

Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Space Administration / The Science and Application Center for Moon and Deepspace Exploration / Emily Lakdawalla

As a result, Chinese have a tradition in pragmatism but not in abstract thinking. Imperial China's scientific successes were in areas of applied sciences such as ship-building, astronomy, agriculture and civil engineering – not in mathematics and natural science. Rao writes:

Did Ancient China have science? Yes, but it was very weak and especially lacking in abstract, systemised, deep science. Some major part is fairly simple, quasi-practical or practical science like astronomy, agriculture, medicine and related sciences.

China "barely took part" in the evolution of science from its origin in Ancient Greece, its transmission to the Arab world and then back to the west.

Observing the systemisation, depth and accuracy of Euclid’s Elements is to wonder whether Western science 2000 years ago was ahead of China 200 years ago... Our pursuit of truth in humanities is very weak and our curiosity towards natural science is also lacking... Attitudes to truth and nature have been major risks of our cultural tradition. Today this doesn't just impact on our science and technology, but on our society as well.

For the first 50 years under communist rule, becoming an official and going into business were high-risk, and so relatively many were willing to take up natural sciences. Many studied maths in particular because it was practical and led to a career, Rao notes, but “not because they want to pursue truth or were curious about nature.”

Only in the early 2000s did the government start putting money into science. And while this has aroused hopes for long-term growth, Rao warns that “for Chinese people, pragmatism prevails, whether at home or abroad.” Even second or third generation Chinese abroad spurn basic science for practical occupations.

The result is that up to now Chinese science "has produced very little original work, or [results] that can directly support industry." Its role in education, in nurturing people who can attract and absorb advanced technology is much bigger than the contribution of original technology.

But the biggest problem is the lack of policies to encourage talent into science and technology.

We Chinese lack a scientific tradition, and as well as our pragmatic culture, science has a short history in China’s development. How we turn around the declining quality of talent and the falling numbers, and stimulate a certain level of high-quality talent to enter science and tech, positively influence China future, is a big challenge.

Robert |

Robert |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  China Science in

China Science in  Innovation

Innovation

Reader Comments